Hope Is the Thing with Feathers by Christopher Cokinos

Author:Christopher Cokinos

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Penguin Publishing Group

Published: 2010-02-26T05:00:00+00:00

The Passenger Pigeon

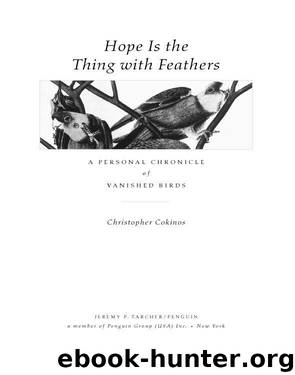

Overleaf: Passenger Pigeons. Note the netting operation in the background. From Thomas Nuttall’s 1840 ornithology.

The Dark Beneath Their Wings

[T]hese birds . . . have communicated to them by some means unknown to us, a knowledge of distant places . . .

—Chief Simon Pokagon of the Potawatomi

IN A VOLUME OF HIS AMERICAN ORNITHOLOGY, PIONEERING NATURALIST Alexander Wilson described a flock of Passenger Pigeons that he had witnessed in the early 1800s as the birds flew between Kentucky and Indiana. The flock, Wilson estimated, numbered 2,230,272,000 birds. “An almost inconceivable multitude,” he wrote, “and yet probably far below the actual amount.” The multitude spanned a mile wide and extended for some 240 miles, consisting of no fewer than three pigeons per cubic yard of sky.

Mathematicians and physicists perhaps can visualize the number, but for years I struggled. Just what was a flock of more than 2.2 billion pigeons like? I needed metaphor. I needed to make the swarm linear. My pocket calculator—good for figuring gas mileage—fritzed as I attempted the equations. So I called on two friends with better calculators. What I wanted to know was this: If the birds had flown single file, beak to tail, how long would the line have stretched?

Assuming each pigeon was about 16 inches long, a line of 2,230,272,000 Passenger Pigeons would have equaled 35 billion inches, or 3 billion feet. That’s 563,200 miles of Passenger Pigeons. In other words, if Wilson’s flock had flown beak to tail in a single file the birds would have stretched around the earth’s equatorial circumference 22.6 times.

Not to be confused with message-bearing “carrier pigeons”—those trained, domesticated birds so useful in war—Passenger Pigeons were wild creatures, prodigious and unequaled. This species once comprised 25 to 40 percent of the total land-bird population of what would become the United States. Historians and biologists have estimated that 3 to 5 billion Passenger Pigeons populated eastern and central North America at the time of the European conquest. The Passenger Pigeon was the most abundant land bird on the planet. The next time you see an American Robin, imagine 50 Passenger Pigeons in its stead; that was the ratio between the two during colonial times.

Jacques Cartier, the first European to write about the pigeons, did so on July 1, 1534, having seen flocks on what is now Prince Edward Island. Champlain saw them at Kennebunkport, Maine, in 1605. De Soto. Mar quette. Sir Walter Raleigh. William Strachey. The pigeons awed them all. “So thicke that even they have shadowed the Skie from us,” marveled one early account. “What it portends I know not,” mused Thomas Dudley of Salem, Massachusetts, on March 28, 1631, after having witnessed a tene brific flight of pigeons.

Flying as low as a few feet off the ground or as high as a quarter-mile, Passenger Pigeons moved in vast congregations that observers compared to squall lines, oval clouds, thick arms and waterfalls. Wilson saw how his flock flew in the shape of a river, then, suddenly, the birds moved into “an immense front.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4799)

Animal Frequency by Melissa Alvarez(4467)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(4314)

Walking by Henry David Thoreau(3956)

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid(3824)

Origin Story: A Big History of Everything by David Christian(3691)

COSMOS by Carl Sagan(3619)

How to Read Water: Clues and Patterns from Puddles to the Sea (Natural Navigation) by Tristan Gooley(3466)

Hedgerow by John Wright(3356)

How to Read Nature by Tristan Gooley(3337)

The Inner Life of Animals by Peter Wohlleben(3315)

How to Do Nothing by Jenny Odell(3297)

Project Animal Farm: An Accidental Journey into the Secret World of Farming and the Truth About Our Food by Sonia Faruqi(3219)

Origin Story by David Christian(3198)

Water by Ian Miller(3181)

A Forest Journey by John Perlin(3070)

The Plant Messiah by Carlos Magdalena(2929)

A Wilder Time by William E. Glassley(2860)

Forests: A Very Short Introduction by Jaboury Ghazoul(2837)